Peer learning is an umbrella term that covers wildly different realities. Taken broadly, it’s about peers - people with the same amount of expertise - learning from each other.

In practice, it’s used to describe learners explicitly teaching other learners, learners working through problems together, learners discussing concepts - experiences that all taste and feel different, and support different learning outcomes.

In this little guide, we’ll describe different practices that fit under “peer learning” and discuss how we can leverage them to meet different experience outcomes.

Experience outcomes

A quick detour before we get into the different practices! To understand what we can do with each practice, it’s useful to identify three types of outcomes we might get from a learning experience:

- Cognitive - the changes that happen in your brain as you integrate new knowledge and become proficient at a skill. It’s what most people picture when they think about learning.

- Social - the construction of a shared understanding and culture around the skills you are developing. For example, children learning their mother tongue not only learn how to speak, they learn how they can affect their environment, using language.

- Emotional - the meaning each learner gives to their learning, mediated by their experience, their mindset, their aspirations, and whether they feel supported along the way.

Having those three outcomes in mind can help prioritise activities when we design a learning experience. For example, if you are creating a short sequence to improve performance in a specific skill, it makes little sense to “waste time” with a predominantly social activity. But if you are creating a program that aims for lasting behaviour change, activities that focus on the cognitive aspect won’t achieve your goals.

The 4 peer learning practices

Disclaimer: the following categories are not meant to be a proper taxonomy, they are simply how I organise my thinking around practices. They are actionable more than theoretical.

Peer teaching

This one is the less peer learning-y of all, because it reproduces a top-down approach to learning, but with a peer instead of a formal teacher.

It’s often misused by putting learners together and hoping that some will know more than the others and that they’ll teach each other. But that’s not peer learning - they are not peers if one knows more than the other.

That being said, when you actually take a peer - someone who has as much expertise as the other students - and give them the task of learning ahead and bringing their understanding back to others:

- It promotes learner autonomy and agency

- For the scout/presenter, it forces them to research, structure and communicate their findings

- Because they have just built their understanding, they will remember the insights that helped them get there and might communicate those better to their peers than the expert teacher

Role of the instructor

With peer teaching, it’s to challenge misconceptions, fill in the blanks, and mediate the peer teacher’s discourse with the practitioner’s insights.

Peer discussion

Peer discussion is the best studied of all, thanks to Eric Mazur - and many physics teachers - who worked on peer instruction 25 years ago. They formalised and researched the effects of peers explaining concepts to each other on their understanding and ability to use those concepts.

Peer instruction (a specific way to structure peer discussion) leaves nothing to chance. The method is structured around ConcepTests, which work like this: the teacher creates questions to address concepts students usually struggle with. Each ConcepTest addresses a single concept. During the lecture, when the time of the ConcepTest comes, students are given 2 minutes to mule over the ConceptTest on their own, they commit to an answer, and then get 3 minutes to debate their answer with their neighbour. The goal is to try and convince the other that their answer is correct. Once the time is up, they either confirm their previous answer or switch to a new one. The teacher gets everybody’s answers, explains the right one, and clears up the misconceptions that showed through the inaccurate ones.

Do you need to spend 10 years carefully refining your ConceptTests to get the benefits of peer discussion? Probably not.

What you do need, and that’s been backed by numerous studies, is to structure the peer discussion. Learners don’t naturally know how to conduct discussions that lead to deeper learning. So, and it’s an extremely important point, you can’t just put learners together and ask them to “discuss now”, you need to decide ahead the ideas that’ll be discussed and in which format.

“[Peer discussion] does not just happen; it requires careful planning and support by the teacher if students are really to develop their cognitive understanding. (…) Learning through discussion does not necessarily produce clear learning outcomes, and the conclusion is therefore that we have to work harder to make sure it is productive.” (Laurillard, 2012, in Teaching as a Design Science)

When peer discussion is properly structured?

- Students are engaged in active processing of concepts and need to find a way to articulate their thoughts, which forces them to refine their understanding in order to communicate it.

- As they share and critique each other’s ideas, they learn to check and confirm their thoughts. It promotes the kind of internal dialogue that leads to deeper and autonomous learning.

- They get to reflect on their own thinking processes in regard to those of others.

Role of the instructor

With peer discussion, it’s to shape the discussion by identifying difficult concepts ahead, to structure student interactions in ways that actively promote learning (having learners take a stand, then debate, then reflect on and negotiate their understanding), and to create a learning community that supports the expression and debate of ideas.

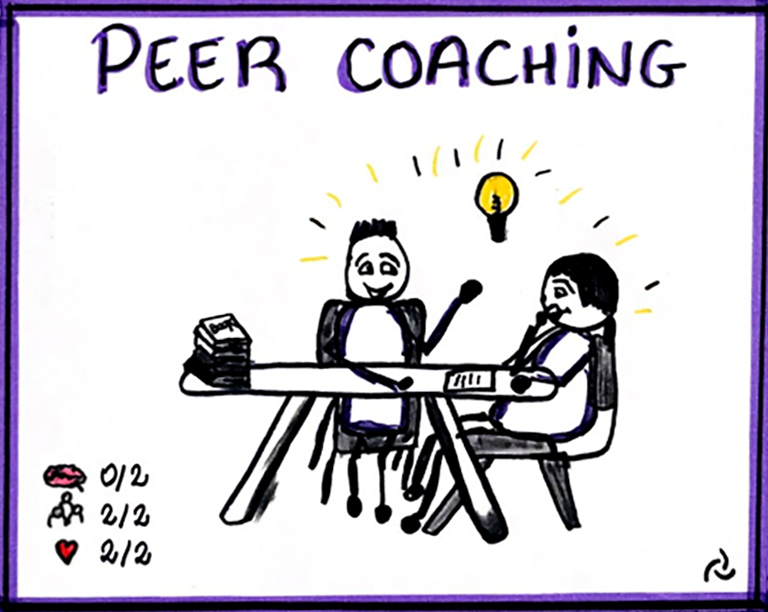

Peer coaching

This might be seen as a special case of peer discussion, but it represents a different purpose within a learning journey. It’s useful to think of it as a separate - and purposeful - activity when we design learning experiences.

Where peer discussion is seen through the cognitive lens of conceptual understanding, peer coaching is more about providing socio-emotional support and modelling. Communication is still the vehicle, but the object is the learning experience itself and how students relate to it, rather than the concepts learnt.

Peer coaching debriefs the learning experience and encourages students to share their learning strategies and the resulting successes or failures.

When peer coaching sessions are effectively implemented:

- They scaffold self-reflection, which is an important part of any learning process but can be difficult to do on one’s own.

- As such, they reaffirm the purpose of learning itself, and support the development of learner autonomy and agency.

- Students discuss and debate habits and behaviours conclusive to learning. They get insights into how others learn, and get to reflect on their own learning habits in regard to those of others.

Role of the instructor

With peer coaching, it’s to scaffold the discussion by providing prompts to explore habits and behaviours, to champion reflection as an integral part of the learning process, and to build a safe environment that facilitates sharing personal insights.

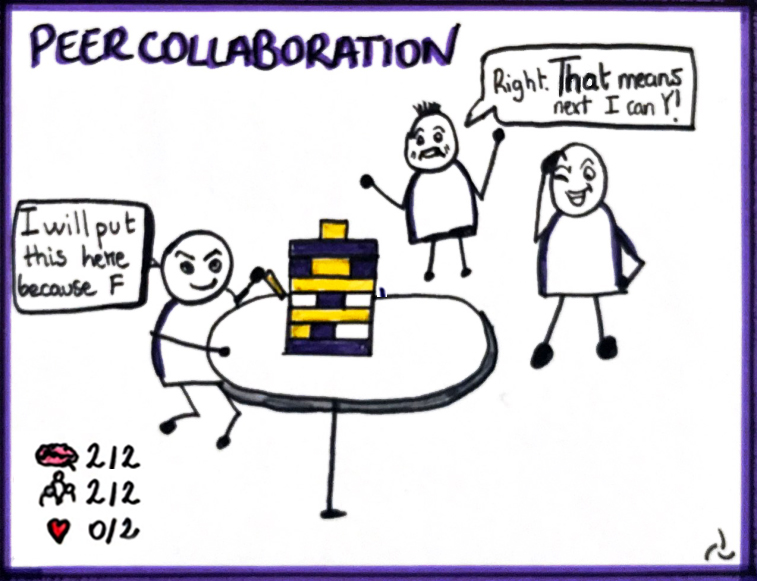

Peer collaboration

Ah, group work!

We’ll leave aside the case when learners each have a responsibility to a piece of the task but each part can be done independently. Picture a 3-floor cake where each student bakes their own floor: this type of co-operative work doesn’t interest us because peers are not required to work together (beyond the occasional synchronisation) to achieve their goal.

Let’s instead consider actual team work, where the group produces something together, and have to co-construct what that something looks like. Taking the example of the cake, that’s when everybody is responsible for the overall taste.

To build something together, they have to agree on what to build, what it means, what quality looks like, how to build it… in other words, they have to construct and improve on a shared understanding of the problem.

When peers actually work through a problem or project together, several things happen:

- They see how others work, talk and think. This gives them models to learn from.

- To come to a shared understanding, they have to express and critique each other’s ideas (they get the benefits of peer discussion, basically).

- Having a responsibility to the group and a shared goal encourages them to work through ideas and to practice together.

“However, empirical studies are also very clear that students have low expectations of collaboration, do not necessarily collaborate just because they are put in a group, and do not necessarily collaborate well, even when they try to.”

Once again, the role of the instructor is crucial to making peers actually learn from each other!

Role of the instructor

With peer collaboration, it’s to structure collaborative processes, to support learners through their construction of a shared understanding (which can include mediating the acquisition of knowledge), and to feedback their shared product.

If you would like to use our LMS with numerous peer-to-peer features, or if you prefer to launch our white-label coding training programs, feel free to come and discuss with us!

Moving forward

Working with any pedagogical technique that gives you less control over what happens in the classroom can be intimidating. If you are not the one explaining or guiding a train of thought, how can you guarantee that learning is happening? That students are going through the experience in a way that’s conclusive for their learning?

And you’d be right to be worried, because numerous studies attest to the fact that peer learning isn’t magic in itself. It needs to be carefully structured (particularly with novice learners), it never ensures proper conceptual understanding (teachers matter!), and it will likely create a lot of resistance from students when initially used.

But it’s also powerful because it teaches students to both value and question their own ideas. By letting the instructor take a step back, it promotes autonomy and student agency.

The key, as always, is in the nuances and not going all-in on peer learning as if that specific approach was the whole solution.

“Argument between students about a topic can be an extremely effective way of enabling students to find out what they know, and what they do not know, but does not necessarily lead them to what they are supposed to know. Discussion between students is an excellent partial method of learning that often needs to be complemented by further explanation or disambiguation from the teacher, if students are not to flounder in mutually progressive ignorance.” (Laurillard, 2012)