Few tools can affect student experience like peer feedback does. Used well, it promotes agency and a growth mindset that’ll transform student outlook on learning - all within a supportive community.

Here I’ll share practical steps to build a culture of feedback. We’ll walk through a framework to learn how to receive feedback and I’ll share the workshop and approach I use when designing collaborative programs.

- Why bother with a culture of feedback

- The problem with feedback (and the solution)

- Workshop template

- Implementing peer feedback consistently

- Last words

Why bother with a culture of feedback

Can you imagine a class where students all feel invested in each other’s growth? A class where students know that feedback is a tool for growth they can use no matter who’s in front of them? A class where feedback is naturally supportive because it’s not a judgment, but a benevolent act?

But feedback is a tricky matter. Because we have seen people get defensive or hurt when we point out things that don’t work, we think we should teach feedback by teaching how to say it nicely.

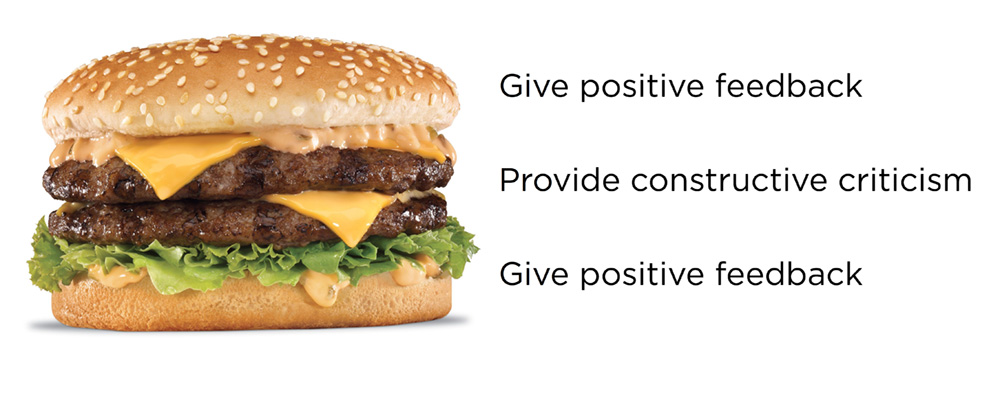

It’s usually done through easy-to-remember techniques such as the feedback sandwich:

What this does, however, is put the receiver at the mercy of whoever is giving the feedback. It’s telling students they’ll get good feedback if they are lucky enough to meet the chosen few who have learnt to give it.

That sounds ridiculous, yet few programs ever touch on the subject of how to receive feedback. Most skip peer feedback altogether because it’s difficult to set up or to see the benefits of. When it’s actually used, the benefits are often framed as a way to lighten teacher workload or to practice critical thinking for students. Very rarely is it framed as the powerful tool for collective growth that it can be.

But a powerful tool it is - and it’s not even that difficult to set up!

To set up such a culture of feedback in your class, you need to do three things:

- Teach learners how to receive feedback

- Design structured feedback sessions into your instruction

- Embody the culture of feedback and consistently show that it matters

The problem with feedback (and the solution)

Feedback is information we get back from the world as a result of our actions. It gives us the opportunity to learn something about ourself and to modify (or continue with) our behaviour.

It’s (mostly) easy to receive positive feedback. People praise our work, our friends are excited to meet up with us, our partner or children smile when they are with us - that feedback feels good, and it’s easy to see the positive outcomes of our behavior.

But when feedback is less than positive, we get confused, irritated, defensive.

Instead of learning from the feedback, we get triggered by it. Our emotions overwhelm us, we are unable to differentiate our actions from our identity (we confuse what we do with what we are), and we feel personally attacked or unheard. You are saying my work is not good? My attitude is not constructive? My jokes are not funny?

But it doesn’t have to be that way.

With practice we can learn to reframe the conversation to extract useful feedback, despite our emotional triggers.

The goal of reframing the conversation is not to ignore our emotional reactions, but to go beyond them. Our emotional reactions are valid, but they prevent us from getting useful information from the situation. They prevent us from growing. They keep us stuck.

There are three types of triggers that prevent us from hearing the feedback (as identified by Douglas Stone & Sheila Heen in Thanks for the Feedback)

Here’s a framework to explore them, identify what each trigger feels like, and see a useful way to reframe the conversation:

Workshop template

This is the approach I use with adult students around their first peer feedback session. It’s best to couple the workshop with the feedback session, when their curiosity in the feedback process is fresh and they are eager to understand how to get better at it!

Here’s the workshop structure:

- 15-min | Introduction to feedback and the growth mindset

- 30-min | First peer feedback session (supported by a script, see below)

- 20-min | Presentation of the triggers framework

- 1-hour | Practicing the framework on 3 use cases (each illustrating one of the triggers): split students into small groups to do 1st use case, discuss with the whole class after 10 minutes, let them do the 2nd one, etc

Presenting the framework after the first peer feedback session allows students to work with insights from their own immediate experience. If they resisted peer feedback - they get to learn why right away!

You could alternatively do the workshop ahead of the first feedback session, and then do a short debriefing after the session.

As an example, here’s one of the 3 use cases I use for tech-related courses:

The goal is to design use cases that are as close to your learners’ context as possible. You want to wire the analysis of the situation to an emotional context they might actually encounter - then, when the situation arises, they will be able to recognise it more easily. (Yay, shortcuts!)

If you have time or if feedback is particularly touchy for your learners, you could role play those activities. It would make it a lot easier for them to identify and discuss the emotions that prevent them from receiving feedback.

Implementing peer feedback consistently

Peer feedback remains difficult to give without directions. You, as the instructional designer, know what the meat of the activity is, and what roadblocks students frequently encounter. Students, unless they are exceptionally perceptive, don’t. For that reason, I prefer to use scripts or rubrics to guide feedback sessions.

A feedback script can be open-ended (to guide a discussion) or reduced to more closed questions (to weight specific aspects).

Open-ended questions are great to debrief work habits or compare strategies without getting into technical details. You can use them after any project or activity, to emulate the kind of coaching that’s hard to give if you don’t have dedicated 1:1 meetings with students.

Rubrics work better to go in-depth over technical points.

In our coding programs we set up peer reviews half-way into projects. We use the exact rubrics that will be used during the final instructor review. This helps students figure out where they are at in regards to the project objectives and to discuss the details of their solutions. On our LMS:

you write the review and configure it as led by staff, scheduled after the end of the project

you clone the review and configure it as led by peer, scheduled during the project (the platform will match peers automatically)

In any case, I do not recommend doing feedback sessions without instructor participation.

If you want students to know that the process matters and is key to their growth, you need to show it. Either be close-by to provide support (at Intek, we had a room used exclusively for reviews and there was always a mentor present in the room during peer reviews), or have group discussions after each session to answer questions and clear misconceptions. It’ll encourage students to trust the process because you “show, don’t tell” that it’s valuable.

Last words

The prerequisite to building a healthy culture of feedback is emotional security.

You can’t plug in peer feedback if feedback is otherwise purely summative or if students are not encouraged to learn from their mistakes. A growth mindset isn’t dependent on one aspect of the classroom, it’s infused in all of its culture.

That being said, when everything else aligns, peer feedback is a great way to develop and reinforce it!